Hurdles Blocking Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the Workplace

“It is important to ensure that diversity and inclusion efforts are not reduced to tokenism, as perceived by minority group members, and are also seen as fair by others in the organization” – Nair & Vohra (2015)

What is Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)?

Organizational diversity refers to differences in race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, physical ability, socioeconomic class and more. The act of equity ensures that processes and programs are fair and provide equal possible outcomes for every individual (e.g. equal pay for equal work). Finally, inclusion practices ensure that employees feel a sense of belonging in the workplace.

Why Engage in Organizational Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)?

Despite ethical motives, research continues to reaffirm the strong business case for DEI in corporate leadership and organizations. Namely a better working environment, from employee commitment and staff retention to deeper trust and untapped talent (different perspectives, knowledge, and skills).

Diverse companies have been found to display multiple perspectives and interpretations in dealing with complex issues, and are better at problem solving and developing new ideas. Research indicates that organizational D&I can boost innovation by up to 20%. Equitable employers outpace their competitors by respecting the unique needs, perspectives and potential of all their team members (McKinsey, 2019). Second, diverse companies are now more likely than ever to outperform their less diverse counterparts on profitability.

Analysis shows that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity on executive teams were 25% more likely to have above-average profitability than companies in the fourth quartile—up from 21% in 2017 and 15% in 2014 (McKinsey, 2019). Third, an inclusive organization is better suited to serve a diverse external clientele in an increasingly global market. Amaram (2007) posits that such companies are likely to have a better understanding of the requirements of the legal, political, social, economic and cultural environments of foreign nations and markets.

Despite these benefits, it should be noted that embedding inclusive behavior may impact organizational performance and cause friction in the short term before ultimately increasing it. However, a lack of inclusivity can degrade performance, demotivate, and damage employee safety and health over time!

Factors Limiting DEI

While it is imperative for organizations to hop on the DEI bandwagon, for both business and ethical reasons, it is also important to understand that the tactics required will be different for each organization. Despite an honest attempt, firms can often fail to successfully engage in DEI due to several limiting factors and unconscious biases, especially during the hiring process or identifying potential leaders. For example, we have a tendency to like things to stay relatively the same (status quo bias).

Given this, organizations may fail to seize diversity when qualified candidates deviate from what a stereotypical, competent employee should look like. Those responsible for hiring and promotions may be prejudiced and gravitate towards applicants similar to them (affinity bias) or reject a particular individual (gender bias, age bias). This could unintentionally result in fewer dissenting opinions within the team (groupthink) when there’s a room full of similar people.

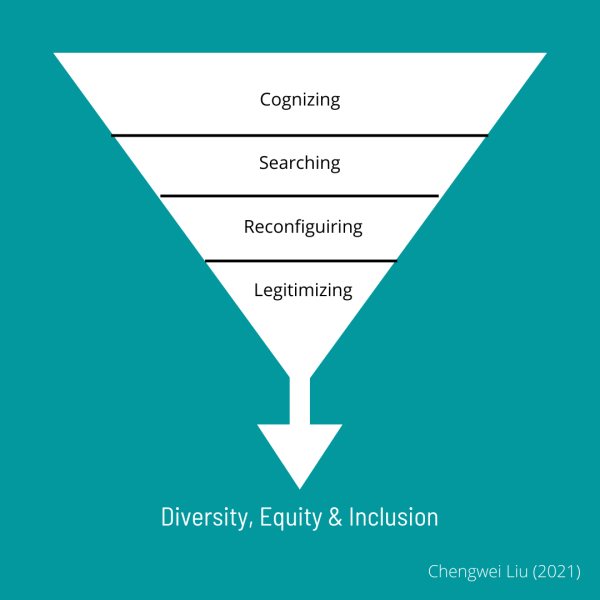

Although uncovering a list of biases may be helpful, by identifying limits like cognizing, searching, reconfiguring, and legitimizing (CSRL; Liu, 2021), we can use behavioral strategy techniques to overcome the behavioral and social limits blocking untapped opportunities. This would help companies easily sense, seize, integrate and justify a diverse and inclusive workforce.

These CSRL limits (Liu, 2021) could be used as an analytical tool to uncover which factor may be blocking DEI, its respective biases, and tailor relevant interventions. You can think of these limits in a filter funnel that organizations get trapped in (see figure 1).

Level 1: Failing to Sense the Need for DEI

The cognizing limit discourages firms from engaging valuable human resources when qualified candidates deviate from what a stereotypical, competent employee should look like according to their mental representations. Which stereotypes are favored is context dependent, but the presence of a widely acknowledged stereotype suggests that many individuals and firms share a similar mental model in that context, which creates and preserves similar blind spots in their evaluations. Oftentimes, we can mistakenly equate identity diversity with cognitive diversity because the former is more easily recognizable and measurable than the latter.

Level 2: Failing to Seize DEI

Even an executive who correctly identifies that the assembled team is insufficiently diverse may be trapped by the “hot stove effect” when searching non-locally (Denrell & March 2001). Executives may be shocked by hiring errors, because attempts to hire a cognitively diverse member usually means experimenting with many atypical hires. Such experiments may lead to long-term performance improvement, but specific hires may cause immediate disasters that prompt the premature termination of searching.

Level 3: Failing to Integrate DEI

Simply including diverse team members is insufficient because of reconfiguring limits. Even when a sufficiently diverse team is assembled, unique perspectives and knowledge may be left unintegrated unless the team has a culture or norm that encourages people to challenge the status quo and value differences. Worse, existing team members may not understand the logic of generating diversity bonuses and may interpret atypical hiring that deviates from objective criteria as discrimination or favoritism, leading to hostility to the new recruit.

For example, recent studies show that when females or racial minorities are hired as executives or chief executive officers (CEOs), they may perform less well than expected because male or white executives may withdraw support due to their perceived loss of identity (McDonald et al. 2017).

Level 4: Failing to Justify DEI

Even when firms have the capacity to sense, seize, and integrate diversity, they may choose not to if doing so would be socially destructive (Benner and Zenger 2016, Correll et al. 2017). External stakeholders may dismiss the boost in performance from engaging diversity if they discount or refuse to acknowledge the process or output. Underutilization, failures, or abandonments after seizing DEI may stigmatize it, preserving it as an apparently unattractive opportunity.

Why does Unconscious Bias Training for DEI Fail?

Considering that leaders and executives are constantly making big decisions, and knowing that human decision making is rife with cognitive biases – merely acknowledging and addressing these cognitive biases blocking DEI is not enough. The field of behavioral strategy advocates systematically removing biases from decision making processes rather than training people to overcome their unconscious biases – a more effective alternative that’s easier to implement.

To mitigate prejudice during hiring and promotions, Dr. Sonia Kang, associate professor at the University of Toronto, recommends the opt out model (Rinaldi, 2022). That is, while evaluating candidates for a senior position, businesses should consider all possible employees for the promotion unless specifically asked to be left out. Thus increasing promotions for female candidates and people of color who would’ve otherwise been neglected due to implicit biases against them.

Kang also recommends applying this opt out model for increasing DEI in other areas like parental leave. Specifically to “reduce the negative impact of parental leave on women.” In some cases, even when companies offer identical leave policies for mothers and fathers, men take less time off. Kang suggests that all new parents should be required to take time off unless they opt out, thus boosting parental leave participation by new fathers and reducing the negative impact of parental leave on women.

Last words…

By placing leadership at the forefront of the DEI effort, we can truly drive a proven methodology for adoption and enablement that focuses on really changing behavior through processes. By focusing on co-creating better decision-making processes, instead of individual biases, we can increase buy-in, ownership, and equity in decisions. Stay tuned for the next article on DEI interventions!

If you want to learn more about behavioral insights,

If you want to learn more about behavioral insights, read our blog or watch 100+ videos on our YouTube channel!

About Neurofied

Neurofied is a behavioral science company specialized in training, consulting, and change management. We help organizations drive evidence-based and human-centric change with insights and interventions from behavioral psychology and neuroscience. Consider us your behavioral business partner who helps you build behavioral change capabilities internally.

Since 2018, we have trained thousands of professionals and worked with over 100 management, HR, growth, and innovation teams of organizations such as Johnson & Johnson, KPMG, Deloitte, Novo Nordisk, ABN AMRO, and the Dutch government. We are also frequent speakers at universities and conferences.

Our mission is to democratize the value of behavioral science for teams and organizations. If you see any opportunities to collaborate, please contact us here.

References:

Amaram, D. I. (2007). Cultural diversity: Implications for workplace management. Journal of Diversity Management (JDM), 2(4), 1-6.

Benner MJ, Zenger T (2016) The lemons problem in markets for strategy. Strategy Sci. 1(2):71–89.

Correll SJ, Ridgeway CL, Zuckerman EW, Jank S (2017) It’s the conventional thought that counts: How third-order inference produces status advantage. Amer. Sociol. Rev. 82(2):297–327.

Denrell J, March JG (2001) Adaptation as information restriction: The hot stove effect. Organ. Sci. 12(5):523–538.

Liu, C. (2021). Why do firms fail to engage diversity? A behavioral strategy perspective. Organization Science, 32(5), 1193-1209.

McDonald M, Keeves GD, Westphal J (2017) One step forward, one step back: White male top manager organizational identification and helping behavior toward other executives following the appointment of a female or racial minority CEO. Acad. Management J. 61(2):405–439.

Nair, N., & Vohra, N. (2015). Diversity and inclusion at the workplace: a review of research and perspectives.